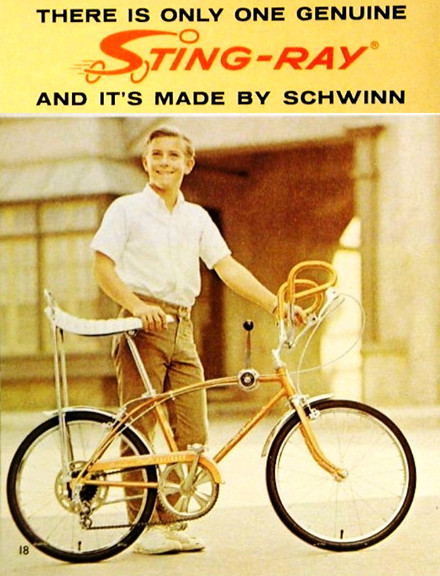

When the Schwinn Bicycle Co. began producing the Sting-Ray

50 years ago this June 1, top executives never imagined that the sporty

two-wheeler with butterfly handlebars and a banana seat would become a national

sensation. Even the company's president playfully bet against its success.

"Before the first model rolled off the line, Frank V. Schwinn saw my

father pull a prototype out of his trunk and bet him $100 it wouldn't exceed

25,000 units in the first year," said Mike Fritz, whose father Al Fritz

designed the Sting-Ray (and died May 7). "Mr. Schwinn had to pay up within

weeks."

As demand for the bike surged—an estimated 700,000 were sold

by 1968—a new demographic emerged: teens who prized standing out rather than

blending in. From the start, the Sting-Ray was geared to budding show-offs.

From 1963 to 1981, Schwinn marketed the Sting-Ray like a

sports car to teens too young to drive. The company even created a line of

aftermarket accessories. In the late '60s, Sting-Ray owners could attach a

tall, chrome "sissy bar" in back or replace their rear balloon tire

with a treadless "slick"—enabling them to leave a patch of rubber on

pavement and fishtail to a stop.

"One of the bike's most attractive features had little

to do with its looks," said David Herlihy, author of "Bicycle: The

History." "On the bike, you could pop a wheelie by pulling hard on

the high handlebars and riding only on the rear tire. The bike gave teens this

outlaw image and helped them get comfortable with fear."

Like many teen trends of the early '60s, the Sting-Ray had

its roots in Southern California. In the summer of 1962, as freestyle dance

crazes like the Twist caught on and the Beach Boys harmonized about hot rods,

enterprising teens in suburban Los Angeles were spotted riding bikes they had

assembled from spare parts.

Huffy Corp.—the nation's No. 3 bike company at the

time—noticed the trend and began producing a black high-rise bike in March 1963

called the Penguin. But Huffy lacked Schwinn's powerful distribution and retail

network. "Al [Fritz] and I went to the West Coast around the same time as

Huffy to see what was going on," said Sting-Ray engineer and Olympic

cyclist Frank Brilando. "The kids showed us their bikes. They had taken

20-inch frames and put on chopper motorcycle handlebars and long seats that

could hold two riders."

When Fritz and Brilando returned to Schwinn's headquarters

in Chicago, they set to work on a design. "Executives were worried the

bike's low pedals might be dangerous on turns, so we adjusted the design,"

said Brilando. "As for the wheelies, we just didn't promote them."

Once the Sting-Ray was launched in June '63, the new bikes

turned heads. "I had one of the first models—it was a dark metallic

purple," said Richard Schwinn, a nephew of Frank V. Schwinn and now CEO of

Waterford Precision Cycles. "It was a big hit, but I was always afraid

kids wanted to be friends with me just to ride it."

Among the first Sting-Ray orders came from George Garner,

who owned three bike stores in the Los Angeles area and was the largest-volume

Schwinn dealer in the country. "I had modeled my stores on car showrooms,

and when kids came in with their parents, they wouldn't look at anything else

except a Sting-Ray," said Garner. "The bikes practically sold

themselves."

In 1968, with color-TVs and muscle cars on the rise, Schwinn

rolled out its Sting-Ray Krate line. Krates came in vibrant colors like apple

red and lemon yellow and the option for a three-speed stick shift mounted on

the frame. The Krates also featured a smaller front wheel, giving the bike a

dragster profile.

By the early '70s, aging teens were graduating to 10-speeds

and discarding their sporty old Schwinns. "A new generation of California

teens hauled those old Sting-Rays out of junkyards and customized them with

shock absorbers and heavier wheels to handle dirt tracks," said Frank

Berto, author of "The Birth of Dirt: Origins of Mountain Biking."

The Schwinn brand is owned today by Quebec-based Dorel

Industries DII.B.T -0.98% and represents a sizable slice of its bike business

in North America—but there are no plans to revive the Sting-Ray.

"It was a cool-looking bike that could do new

things." said Eric von Hippel, professor of technological innovation at

the MIT Sloan School of Management. "But it also became an innovation

platform for the next generation of teens, who moved the industry to the next

big thing—all-terrain biking."

No comments:

Post a Comment